Summertime, in the eighteenth century, was no time for eating fresh pork. The oppressive heat that made quick work of humans in the Middle Atlantic colonies also turned the choicest cuts of meat into Petrie dishes of corruption. The day a pig was slaughtered, it was cooked and eaten, often as part of a family celebration or for the arrival of important visitors. Leftover meat was quickly shared with neighbors or slaves.

A frosty month, especially December, was the proper time for pig butchering, salting, and smoking. It's a tradition documented to medieval times. The illuminated manuscripts known as books of hours, prestige prayer books, often depict pig slaughtering on their calendar page for December, in the same way that they show planting in March and harvesting in August. Killing the winter pigs was just another part of the annual agricultural round.

If you expected to have pork all year long, you needed a smokehouse. From earliest times, a smokehouse was a small enclosed shelter, a place in which a fire could be kept smoldering for a few weeks, which would only slowly release its smoke, and in which the smoked meat could hang safe from vermin and thieves.

Just about any sort of vernacular shed could serve. But an elegant Gothic one appears in a book of hours painted in France by the so-called Rohan Master about 1420. On the page for December, a pig is being slaughtered, a wooden tub sits ready for the salted meats, and a fire has been kindled in the little smokehouse. Not that all those necessary tasks are meant to happen on the same day.

In essence, you cure meat in two steps. The fresh cuts are packed in tubs of coarse salt for about six weeks while the salt draws most of the water from the flesh. Then the salted meats are hung in a tightly constructed wooden shed, usually without windows or a flue, in which a fire smolders for one to two weeks. The result is dried, long-lasting, smoke-flavored meat that will age in the same smokehouse for two years before it's eaten.

Smokehouses don't show up in the documentary or archaeological record of seventeenth-century Tidewater. If they're smoking meat at Jamestown, they're doing it in ephemeral sheds or barns, not in purpose-built structures. Or the task may have been done as it often was in England, in smoking closets tucked away inside chimney flues. But since so very little remains of Jamestown above foundation level, it's impossible to know for sure.

By the first half of the eighteenth century, a new class of building is regularly appearing in the backyard landscape: the smokehouse, alternatively spelled "smoak" house. Typically, these are cubical structures of wood, eight to fourteen feet square, with steep pyramidal roofs for holding in the smoke among the hanging cuts of meat. It's at this time that the word first shows up in written records, according to the Oxford English Dictionary and Carl R. Lounsbury's Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape.

In 1716, there's a mention of a smoak house on a plantation in York County, Virginia, the earliest known use of the term. A Hanover County plantation listed for sale in the Virginia Gazette on January 7, 1742, points to its "new fram'd Smoak-house, 8 Feet Square." In 1732, "a Smoak house eight foot square" with a "planked Dore," is ordered for the glebe of Newport Parish, Isle of Wight County, Virginia. The sturdy door is to do with security. After the fires went out, the meat was stored in there. Poachers had to be kept at bay.

Everyone needed a smokehouse. At Colonial Williamsburg, of the eighty-eight original structures that survive, twelve are smokehouses. And an additional fifty reconstructed smokehouses dot the backyards of the Historic Area, many built atop the foundation footprints of likely smokehouses. At the Governor's Palace, the Wythe House, and the Peyton Randolph House, reconstructed smokehouses are still used to cure and flavor pork.

Sometimes a smokehouse is also called a meat house, which makes sense because the building spends much more of its time as a storage locker than it does as a smoking house. In 1778, a house on Custis Square in Williamsburg is said to come with a meat house. In Maryland, the phrase "meat house" seems to be preferred over smokehouse. In Sussex County, Delaware, however, there was a farm with a meat house and a smokehouse, according to an Orphans Court valuation of 1812.

In Virginia, meat house is the exception. In the List of White Persons and Houses taken in the County of Halifax, 1785, there are fifteen "smoak" houses and one meat house. This record is useful for looking at smokehouse sizes: Of the fourteen Halifax structures the dimensions of which are listed, five are twelve-by-twelve feet, five are twelve-by-ten feet, and the rest are twelve-by-eight, ten-by-ten, eight- by-eight, and sixteen-by- sixteen. They must have seemed like near-perfect little cubes, part of an impressive parade of useful and well-made outbuildings in the colonial backyards, the hallmark of a society that wanted to be seen as tasteful, well managed, civilized.

A sense of how the smokehouse was made and used is plain in Thomas Cooper's report of what life was like on the ground in North America, in a book published in London in 1795. He's describing the large plantation of one Archibald M'Allister in Paxtang, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania:

His smokery for bacon, hams, etc. is a room about twelve feet square, built of dry wood a fireplace in the middle, the roof conical, with nails in the rafters to hang meat intended to be smoaked. In this case a fire is made on the floor in the middle of the building in the morning, which it is not necessary to renew during the day. This is done for four or five days successively. The vent for the smoke is through the crevasses of the boards. The meat is never taken out 'till it is used. If the walls are of stone, or greenwood, the meat is apt to mould.

All this rings true and speaks to several design commonplaces in historic smokehouses. Carl R. Lounsbury, an architectural historian at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, thinks the centrality of the heat source, a firebox in the middle of the floor, drives the building's square shape. And the sharply pitched roof is essential for containing heat and smoke.

Water inside the meat is a problem. It spoils everything. Dried meat lasts longer. And so the heat and smoke are meant to drive off the water. "Some smokehouses have a small square fire pit; some have bricks covering the floors; some have plain dirt floors," Lounsbury says. The more intricate the roofing timbers, the more places to hang meat. "Sometimes," he says, "you find extra collar beams up there. And we've seen all manner of pegs, nails, hooks, and chains for hanging meat."

Another way of removing water is with salt. The job starts by working a mixture of twenty-five pounds of salt and two pounds of brown sugar deeply into every inch of the fresh meat. Two ounces of saltpeter are added so the meat will retain its pinkish color. It's a tough job that can only be done by hand.

At Colonial Williamsburg, the second Saturday of December is the traditional day for salting pork. "After the hand salting," says food historian Frank Clark, "we dry pack the pork in tubs, forcing the meat and coarse salt in as tightly as we can. Each tub has several large holes in the bottom for the 'liquor' to drain out into the dirt floor." That liquor is the unusable and faintly-not-nice water drawn off by the salt. It's dehydrating the meat, replacing water with salt. The tubs appear to be truncated half-barrels, resembling the wooden tub in the Rohan book of hours, a scene nearly six hundred years old.

The colder the weather, the slower the liquid flows out of the meat. Still, after about six weeks in the salting tubs, the cuts are ready for hanging over the smokehouse fire. At Colonial Williamsburg, the fire is usually kindled in February. Because the whole point is smoke, not flame, green wood is used, though historically corncobs or fruitwood smoked well enough. At Shirley Plantation, whose smokehouse was last used in about 1953, apple wood was burned, according to proprietor Hill Carter. It added a special sweetness to the meat. Also at Shirley, the fire was allowed to burn untended day and night. It was relit every morning. "It wasn't a disaster if it went out," Carter says.

Typically, smoking would last about two weeks. The reconstructed Wythe smokehouse is so solid, its wallboards so tightly fitted, it's more like a piece of outdoor furniture. It holds in its smoke well and is the most efficient smokehouse in town.

The more vernacular smokehouse behind the Peyton Randolph House leaks profusely. In keeping with that backyard's orientation, the smokehouse uses two types of boarding on its four sides: sawn poplar weatherboards for the sides facing the house and more formal yard but riven oak clapboards for the sides invisible from the house. Wool has been stuffed into the crevices between the irregular clapboards. With more oxygen getting inside this smokehouse, its fire burns brighter and faster, but it loses so much smoke it takes much longer to cure the meat.

More smokehouses were like the Peyton Randolph version than the Wythe's. People who grew up around working smokehouses a half century ago recall the comforting sight of them in the landscape, puffing away at their wintery task like steam engines.

Not that smoke is an unalloyed blessing. Inside an old smokehouse, the studs and walls appear black and shiny, like the oily-feathered back of a grackle, the layer of creosote deposited by years of smoke. And since the hams, shoulders, and bacons age inside the smokehouse for at least two years, they can be exposed to several more rounds of smoke. Creosote begins to coat the meat. This may be why, at Shirley, cured meat was removed from the smokehouse and rehung in the basement of the big house. "Some of it went three to four years," Carter says. "Some of it the rats got."

Since insects, too, have a taste for bacon, the tighter the smokehouse, the better. But some always managed to get inside. For them, the cured meat was coated with pepper, a natural insect repellent. Hickory ashes were another way of discouraging bugs.

A smokehouse that's too tightly constructed can be trouble. Elevated humidity inside can lead to gray and green blooms of mold on the hanging meat. "You have to be careful about bright molds," Clark says. "Bright greens or purples can be nasty. The duller molds and the creosote can just be washed or cut off the meat. No harm done."

Salt, though lovely for meat, is a problem for smokehouses. After a century or more of use, the wood cells of timber get infused with salt, which replaces their water, and the studs go all fuzzy and soft. Deep down the wood can be fairly competent, but the surface is pure Nerfball.

Brick smokehouses are especially threatened by salt intrusion. Lavishing the investment of bricks on a utilitarian building devoted to a smoky, almost industrial use was pure ostentation. Still, stunning examples of brick smokehouses exist at Shirley, at His Lordship's Kindness near Clinton, Maryland, at Reynolds' Tavern in Annapolis, and at the Benjamin Powell House at Williamsburg, to name a few.

They're unusual, if not quite rare, often plagued by salt intrusion that leaves the bricks and mortar friable. Decades of degradation have given the bricks the rounded and insubstantial appearance of damp sugar cubes. The Powell smokehouse had gone so granular that hundreds of finches were pecking it away, either for the salt or for the tiny stone grains they use in digestion. The solution was to blot the building with seven applications of a shredded-toilet-paper poultice, which drew out thirty-eight pounds of the offending salt.

At Shirley, the solution was to render the walls with a covering of cement stucco, a fix that was tried at the Powell House in the 1820s but was removed in the restoration of the building in 1956. The Shirley stucco is still in place, still doing its job.

So what is it all about, this quest to understand smokehouses and to reconstruct them in believable ways that reflect eighteenth-century life? For Edward A. Chappell, director of architectural research at Colonial Williamsburg, God is no longer just in the details.

"We won't copy bits of a historic smokehouse for a reconstruction," Chappell says. "We try instead to understand the system: how and why and where this building was built, how it fit into a complex zone of backyard activities. Building details are helpful, but the relationship between buildings is what's most interesting. So we record the whole plan of the farmyard during fieldwork, not just louvres and hooks and hinges."

The reconstructed Peyton Randolph smokehouse is an example of an older building that got a facelift when the family began to transform its property in the 1750s. Its clapboard sides, facing away from the house, were refitted with more finished and expensive weatherboards.

"In time, we came to understand," Chappell says, "that in the Peyton Randolph backyard there was a palpable division of activity. Zone A was for clean work; the dairy was there. Zone B was for more unsavory and industrial work. And although the smokehouse is more or less balanced by the dairy, its door shouldn't open into Zone A. There's even a fence between the two zones."

And so the door will be moved from the south to the north side of the smokehouse, opening into zone B, not into the cleaner zone, near the slaves working in the laundry and kitchen and the Randolph women making butter and cheese in their spotless dairy. It's a change driven by new archaeology and a clearer understanding of this particular backyard.

There was once a time when these zones, these interdependencies, defined people's lives. There were always distinctions between the field and the house, of course. But these new fences, these mute zones centered on the smokehouse and the other backyard outbuildings, they were there too, a real part of the circle of common knowledge we are only now uncovering. It was a world built on boundaries.

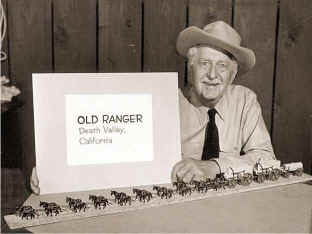

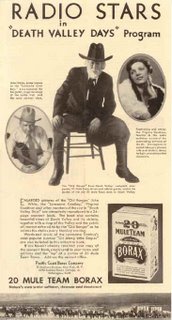

Ruth Cornwall Woodman, a Vassar graduate and mother of two children, was hired by the Borax Company and its advertising agents, McCann-Erickson, to write the “audition” script for Death Valley Days. What started as a one-time assignment became a career -- she was asked to stay on to write all of the radio plays.

Ruth Cornwall Woodman, a Vassar graduate and mother of two children, was hired by the Borax Company and its advertising agents, McCann-Erickson, to write the “audition” script for Death Valley Days. What started as a one-time assignment became a career -- she was asked to stay on to write all of the radio plays.