By M.L. LYKE of the SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER REPORTER

By M.L. LYKE of the SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER REPORTERTuesday, March 28, 2000

Don Klein is a down-home sort, a plain-talking, snoose-chewin' retired dairyman who describes himself as a Ford man and "an honest Dutchman."

Decor in his Arlington farmhouse is strictly cow-&-country, with pictures of his prize-winning jerseys on the wall, a wood pellet stove for heat, and racks of mesh baseball caps gathered over decades: There's The Whey Man hat, a B.T.F. Trucking and Hay Sales hat, the goin'-to-town Land O' Lakes hat, and a hat with two lusty elk makin' bacon.

The tools of his controversial calling aren't highfalutin either: a vine maple branch with a slingshot crotch, the sucker off an apple tree, steel survey stakes.

But there's something else at play here. Something intangible, mysterious. Call it a gift. Call it voodoo, as some skeptical geologists do. Or call it The Force.

Resistance is futile. Or so say local practitioners of the ancient art of water witching, who describe tightly clutching sticks that suddenly pull, twist, jerk and wrench as they pass over underground water deposits.

"My hands have been rubbed raw from the sticks," says Klein, one of the region's better-known witches -- also called dowsers or diviners. "If it's a strong vein of water, it can break the stick."

White-knuckling his forked stick, eyes clenched in concentration, Klein has dowsed for real-estate developers, well drillers, Microsoft executives and other private property owners, from doctors to county building inspectors.

"There's probably not a driller in Snohomish County who hasn't used him," says Greg Halverson at Affordable Water Systems in Mount Vernon.

Klein's most recent job was witching water for a new real-estate development on a sheer bluff above the Stillaguamish River.

"They had one well up there at 400 feet, and they were sucking sand," says the retired dairyman, whose earnest little Winnie-the-Pooh eyebrows dance above oversize glasses. "I've got two up there so far, one at 130 feet and one at 116 feet, and they've both got all kinds of water."

Klein is one of a handful of local witchers who purport to not only locate underground water, but to estimate its depth, describe the rock and soil layers above it, and gauge the number of gallons per minute that a well might yield at the site.

The forked stick is his locator. He uses the survey stakes to mark the drilling site -- often at a spot where he says two underground water sources cross. The apple-tree sucker is for estimating depth and soil conditions.

He sets the flexible sucker in motion, judging the depth of the water by the number of bounces. If the bouncer stick slows, he says, it could mean there is hard pan or heavy clay below. "If there are small boulders, it will twirl. And if it stops, there's a good chance it's a big boulder."

Klein does up to a hundred witchings some years, many at the behest of well-drilling companies whose clients request a dowser. When a 400-foot hole comes up dry, it can drain the pocketbook some $10,000, and many new property owners are eager to hedge their bets before the digging begins.

At $75 to $150 a pop, a witching session may seem a bargain.

"It's not that it's 100 percent, but it's another ace in the hole," says Halverson. The Mount Vernon well driller estimates about 30 percent of his sites have been dowsed before he starts to work -- sometimes by a family member, sometimes by a known witcher like Klein.

"Most of the time, people think they can do it, but they really can't," says Halverson.

Dowsers have different reads on who, exactly, has "the gift."

The American Society of Dowsers maintains everyone is born with the capability. But Joe Nunes, a Camano Island well driller who does double-duty as his own witcher, estimates only one in a thousand can do it.

Klein isn't sure. He has been witching almost 40 of his 62 years, and learned it from his brother. He tried to teach his own children, "but it just doesn't work for them. Why, I just don't know."

Maybe The Force is with him.

Maybe he is the force.

Professional skeptic James Randi, a former escape artist dedicated to debunking paranormal claims, attributes the witching phenomenon to what he calls the "ideomotor effect." He suggests that an idea or thought process evokes an involuntary body movement in the dowser, and the dowser unknowingly exerts a small "shaking, tilt or pressure" to the witching device.

Controversy has followed dowsing throughout its tangled history. The earliest records of water witching are 6,000- to 8,000-year-old cave paintings in Africa that are believed to show a figure with divining rods.

The first detailed description of the practice was in a 1556 description of mining techniques in Germany. Mineral dowsing was adapted to water dowsing during the reign of Elizabeth I in England.

Many modern-day critics call dowsing a superstitious relic, a delusional pseudoscience, a deliberate sham.

"For a driller to witch for water or to recommend a witcher is as reprehensible as for a doctor to be or recommend a quack," writes geologist E.H. Boudreau in a widely circulated article for the Northern California Real Estate Reader.

A U.S. Geological Survey pamphlet on dowsing notes that the practice has been almost unanimously condemned by geologists and technicians. Many cite experiments that show dowsers scoring little higher than random guesses in controlled conditions.

"The natural explanation of 'successful' water dowsing is that in many areas water would be hard to miss," states a USGS pamphlet on dowsing.

Unearthly explanations don't sit well with earth scientists.

"As a trained water person, my opinion of someone locating water 300 to 500 feet underground holding a willow stick is that it's pretty much voodoo," says Jim Ross, a hydrogeologist at GeoEngineers in Redmond.

Even property owners who call in a dowser may be skeptical.

"There are a lot of people who don't believe it, a lot of people who are afraid of it," says well-driller/witcher Nunes, at Camano Well Drilling. "They believe it after they spend $30,000 to $40,000 and still don't find water. Then I come in and find 'em a well."

Despite centuries of condemnation, dowsing remains very much alive, and very little changed, in an age of fast-forward technology.

Dozens of countries have dowsing societies, from Britain and India to Argentina and Austria. The dowsers of France have a national union. A team of German scientists has combined water engineering with dowsing skills to locate village wells in historically difficult, semi-arid regions of developing countries.

The practice is all over the map, but so are the practitioners.

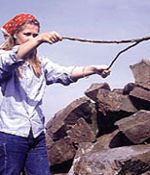

Dowsers seldom agree on the hows, whats and whys of witching. Some use metal L-shaped rods of copper or steel, gripped tightly below the bend. Some insist on traditional Y-shaped sticks, often limber branches of willow, peach or witch hazel. The sticks are held stem-to-sky, hands clutching the forks, palms up.

"The forked stick is the true test," says Nunes. "You put tension on the stick so it kinda bows, squeeze as tight as you can and start walking. The stick actually twists in your hand."

But does it go up or down?

The stem of Nunes' "Y" heads to the sky. Klein's heads to the earth. There are similar discrepancies with the L-rods. Some dowsers' metal rods will cross, some will fly backward.

Nor are rods the gold standard. Keys, scissors, wire coat hangers, pliers have all been used to dowse. And some dowsers use pendulums -- maybe a simple hex nut secured on a string -- or bobbers. A bobber might be a fresh shoot off a tree, a sturdy wire, even the plastic tip of a fishing rod.

Some practitioners claim to enter into an alpha state, or a trance, to dowse. Even Klein holds mental pictures in his head as he witches.

"When you're doing it, it's a state of mind," he says. "It's what you're thinking is what you get."

But few agree on how far a witcher's powers extend.

The psychic Uri Geller -- whose spoon-bending tricks were challenged by skeptics -- reportedly found riches for international mineral companies simply by dowsing a map. Map-dowsing for buried treasure, or veins of gold, or even water, is still a hot topic.

Some witchers claim to locate human bodies, find downed planes, track storms, dowse for disease in a human body, analyze a person's character, determine the sex of an unborn child, determine if signatures are forged, or track submarines.

Fred Welk, a witcher based in Medina, belongs to a decidedly more modest school.

Welk claims only to find water. He doesn't do depth. He doesn't do soil. He doesn't estimate gallonage. And he doesn't form pictures in his head. He just grips his L-shaped copper rods and lets them do the talking.

"They've got to do whatever they do, no matter what I'm thinking about," says the tall, fit, white-haired 78-year-old retiree.

What they do is whang back at 90-degree angles as he locates an underground spring. Welk delicately dances back and forth over the site, a Fred Astaire for the wet set. The rods flap like elongated arms with each motion. "You can feel it. Whatever forces there are, they are there," he says.

Welk has a Web site (www.icatmall.com/waterwitcher), but like most local witchers, he gets the bulk of his clients from word-of-mouth recommendations. "The bad part of it is so many people call after they have already spent $4,000 or $5,000 drilling at random. In desperation they call around and find my name."

One of his clients is Lynn Cash, who called on Welk after watching her neighbor in Woodinville drill three dry holes before finding water -- at a cost of $28,000.

"I was really doubtful of the whole process," says Cash. "I thought, well, I'll give it a shot. Otherwise, you're just taking a chance.

"We found water, and it only cost us $6,000."

Fred Welk has a theory that the powers of witching have to do with electrical currents coursing through human bodies. As evidence, he holds two wires attached to an ohmmeter. The needle flies far to the right.

Others suggest the attraction has to do with empathy, magnetic fields, the chemistry of a body, or simply belief.

"Water doesn't really attract anything," says Gene Hitt, at Gene's Well Drilling in Stanwood. "I don't care if you use a stick or wires -- but if someone believes, you aren't going to change their mind."

Certainly no one is going to change the mind of Tom Leary, at Leary Construction Company in Ballard. The water-main contractor keeps a set of witching rods on his backhoe at all times. And he's not apologetic.

"People think you're crazy, but we use them all the time," says Leary. "When I dig down, I want to make sure there is something there."

The contractor uses welding rods bent into the L shape to search out the water mains that evade their metal detectors.

When he hits water, says Leary, "it whips 'em right around."

He doesn't guess at the reason. "I don't know. I really don't."

But he likes the results. "We're right on the money with it most times."

And most times beats the alternative.

No comments:

Post a Comment