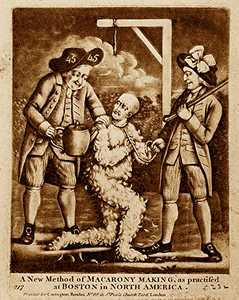

The practice of smearing a body with tar and then sprinkling the tar with feathers was not original to America. As long ago as 1189, during the reign of Richard the Lionhearted, it was prescribed in the British navy as punishment for theft. But English colonials brought it ashore in North America and made such use of it that it now is thought of as American. It was described as the "present popular punishment for modern delinquents" in 1769.

Richard Thornton's 1912 American Glossary has more than a dozen examples of tar and feather for the years 1769 through 1775, starting with a newspaper account from October 30, 1769. "A person," reported the Boston Chronicle, "was stripped naked, put into a cart, where he was first tarred, then feathered." The Newport Mercury for December 20, 1773, carries a "Notice to the Committee on Tarring and Feathering": "What think you, Captain, of a halter round your neck--ten gallons of liquid tar decanted on your pate--with the feathers of a dozen wild geese laid over that to enliven your appearance?"

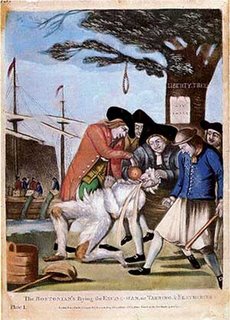

During the American Revolution, rebels made examples of British loyalists by tarring and feathering. A memoir of 1774 refers to "the Liberty Boys, the tarring-and-feathering gentlemen." That year a notable victim was "Mr. John Malcomb, an officer of the customs at Boston, who was tarred and feathered, and led to the gallows with a rope about his neck."

The practice was occasionally very violent and resulted in death, but most of the time the purpose was humiliation. John Robert Shaw, in his autobiography from this period, tells a story of a light feathering from New Bedford, Massachusetts:

In this excursion, among other plunder, we took a store of molasses, the hogshead being rolled out and their heads knocked in, a soldier’s wife was stooping to fill her kettle, a soldier slipped behind her and threw her into the hogshead ; when she was hauled out, a bystander then threw a parcel of feathers on her, which adhering to the molasses made her appear frightful enough;–This little circumstance afforded us a good deal of amusement.

The prohibition in the 1791 Bill of Rights against "cruel and unusual punishments" may have helped discourage the practice of tarring and feathering, which seems to have vanished by the end of the nineteenth century. Tar and feather remains in our language today, but only as a figure of speech for public humiliation.

No comments:

Post a Comment